Part 1: Why Community Infrastructure Matters

Why community infrastructure matters

Community infrastructure is broad. It can include parks, sports fields, libraries, community centres and arts and cultural spaces. These places shape how healthy we are, how connected we feel and how liveable our neighbourhoods become.

Despite this, community infrastructure is often treated as secondary to roads, utilities or transport when cities grow. Homes are built quickly, but the places that support community life arrive late, arrive small or sometimes do not arrive at all. The cost of delay is not only financial but also lived. Waiting 10 years for a park can mean missing an entire childhood.

This raises two urgent questions. How important is community infrastructure, and what is the cost of not caring?

We scoured work already done in the space and lay out the key findings here.

1. How important is community infrastructure?

Economic Value

Community infrastructure delivers strong economic returns. Across Australia, sport and recreation infrastructure adds about $6.3 billion to the economy each year and supports around 33,900 full-time jobs1.

Figure 1: Economic Value of Community Sports Infrastructure

Key community infrastructure such as libraries show a very strong socio-economic return. For example, Victorian public libraries generate around $4.30 of economic value per $1 invested2.

When you place these results alongside major spending on transport or housing, it’s clear that community infrastructure can deliver equally if not greater value. For instance, Sydney Metro City and Southwest posted a benefit–cost ratio (BCR) of 1.5 in its final business case3. Meanwhile, Victoria’s Suburban Rail Loop East was assessed with a central estimate BCR below 1, meaning its costs exceed its benefits4.

Housing investment also delivers strong results. For example, NSW’s Social and Affordable Housing Fund (SAHF) produces BCRs of 1-3 once avoided service costs are included5.

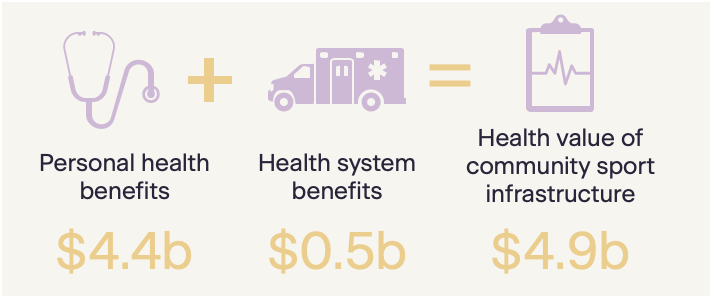

Health and Wellbeing Returns

Health benefits are just as strong. Community sport recreation infrastructure saves the health system about $4.9 billion each year across Australia2.

Figure 2: Value of Health Benefits

If everyone did just 15 more minutes of physical activity a day, it could prevent an equivalent of 32,000 years of healthy life lost. As well as prevent a projected 1,600 early deaths by 2030. It would also lift productivity and reduce pressure on hospitals and health services6.

Compare this with other sectors. A new regional hospital typically returns a BCR of around 2.0. Justified through avoided deaths and better care access7. In dollar terms, that means a $500 million hospital investment might generate roughly $1 billion in net benefits through avoided deaths and improved service access.

Community infrastructure, by contrast, functions as preventive health infrastructure. Parks and recreation assets cut disease before it ever reaches the health system.

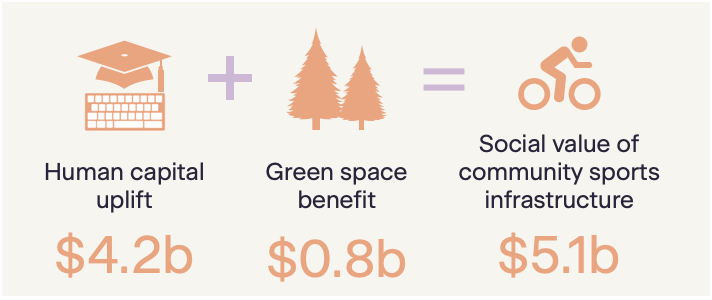

Significant Social Dividends

Community sport recreation generates about $5.1 billion in annual social benefits, with human capital uplift valued at about $4.2 billion2.

Figure 3: Social Value Benefits from Sports Infrastructure

- Community infrastructure also delivers forms of value that markets often undercount.

- Victorian libraries generate more than $4 in value per $1 invested, much of it in literacy and digital inclusion3.

- A national review of the Community Hubs Program in 2023 found that for every $1 invested, the return was $3.508.

- Cultural venues and local events, for example, the Australian Museum’s Ramses exhibition returned more than $11 for every $1 spent. This delivered $57 million in benefits for NSW9. This shows what targeted cultural investment can achieve.

2. What Is the Cost of Not Caring?

Health and Wellbeing Costs

Under-investment shifts avoidable costs to the health system. Physical inactivity and related risks drive large, preventable spending and lost healthy life.

- Inactivity and obesity already account for over 10% of Australia’s disease burden10. Without accessible facilities, those costs grow each year.

- In 2018–19, an estimated $2.4 billion was spent on health conditions due to physical inactivity, including $1.7 billion directly from inactivity. And about $766 million indirectly through other risk factors such as high blood pressure attributable to insufficient activity11.

- By comparison, Infrastructure Australia (2019) reports that regional hospital projects typically deliver BCRs of around 2.08. In dollar terms, that means a $500 million hospital investment might generate roughly $1 billion in net benefits through avoided deaths and improved service access.

How do the two compare? Hospitals are vital for treatment, but their benefits flow once illness has already occurred. Community infrastructure can prevent much of that illness in the first place. Potentially avoiding billions in costs each year, not just hundreds of millions over a single hospital’s life. In other words, the dollar-for-dollar returns of community infrastructure in preventive health rival, and in some cases could surpass those of major hospital builds.

Social Isolation

- Every year it costs Australia about $2.7 billion or around $1,500 for each person affected, as more people rely on health and social services that could have been avoided12.

- Housing programs such as NSW’s SAHF achieve billions in avoided costs and BCRs of 2–3 for the most part through health and justice savings7. These outcomes are valuable, but they do little to reduce the experience of isolation. Secure housing does not guarantee social connection.

- Housing provides stability, but by itself it cannot solve loneliness. Community infrastructure takes on that $2.7 billion problem directly. At the neighbourhood level, hubs and gathering spaces deliver connection and belonging in a more cost-effective way than any other option.

Productivity Drain

- Victorian modelling shows that physical activity infrastructure unlocks $3.1 billion in lifetime productivity benefits, but only if facilities are close and accessible8.

- Nationally, absenteeism linked to inactivity and poor health costs businesses $14.1 billion in 2022 and projected to hit $24.2 billion by year's end13.

Congestion

Without local facilities, families travel (drive) further for everyday needs, worsening congestion.

- National estimates put the avoidable costs of congestion at $16.5 billion in 2015, rising to $30 billion by 203014.

A single well-placed community hub or park removes thousands of unnecessary car trips. This eases congestion more cheaply than a motorway. Compared to housing, the trade-off is also stark. Estates without facilities externalise travel costs onto the road network, inflating congestion costs for everyone.

Pressure of Density

As more Australians live in apartments and townhouses, the absence of nearby parks and hubs creates measurable risks.

- High-density neighbourhoods without green space see more stress, poorer outcomes for children, and higher health costs15.

- International evidence shows that green infrastructure delivers benefits between $2 and $11 in health and well-being for every $1 spent16. However, housing programs like the SAHF return about $2–$3 for every $1 invested. While this is valuable, the benefits are significantly lower than green infrastructure.

How do they compare? Housing delivers a basic human need - i.e. shelter, but green space keeps communities healthy and to deliver strong returns on every dollar invested.

Conclusion

So how important is community infrastructure? The evidence is clear. Every $1 invested returns many more in health, social and economic benefits. The multipliers for parks, libraries and hubs are comparable to and can be higher than those for roads, rail and even housing programs. This is not an either-or proposition. The much-needed investment in housing and transport to enable growth has to be supported by appropriate and timely community infrastructure.

And what is the cost of not caring? It is measured in billions of dollars in preventable health costs, lost productivity, social disconnection, congestion and declining liveability. It is felt most sharply in fast-growing suburbs where residents can wait years for basic infrastructure, effectively living at a discount.

The choice is simple. We either invest in community infrastructure now or pay the price later in rising health bills, weaker productivity and lost childhoods.

References

1 KPMG (2018). The Value of Community Sport Infrastructure. Sydney: KPMG.

2 SGS Economics & Planning, (2018). Libraries Work! The socio-economic value of public libraries to Victorians.

3 NSW Parliament (2019). Sydney Metro City and Southwest: Final Business Case.

4 Parliamentary Budget Office (2022). Suburban Rail Loop East: Budget and Economic Analysis.

5 NSW DCJ (Department of Communities and Justice) (2025). Social and Affordable Housing Fund (SAHF): Evaluation and Outcomes Report

6 Marsden Jacob Associates (2020). The Economic Impacts of Active Recreation in Victoria.

7 Infrastructure Australia (2019). Health Infrastructure Assessments – Regional Hospitals

8 Deloitte Access Economics, (2024). Community Hubs Australia-Social return on investment evaluation of the National Community Hubs Program

9 Australian Museum, (2024). Ramses & the Gold of the Pharaohs: Economic Impact media release.

10 AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2019). Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Australia 2018

11 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, (2023). Economics of sport and physical activity participation and injury

12 Duncan, A., Kiely, D., Mavisakalyan, A., Peters, A., Seymour, R., Twomey, C. & Vu, L.L., 2021. Stronger Together: Loneliness and social connectedness in Australia

13 Frost & Sullivan (2022). Workplace Absenteeism in Australia: Costs and Forecasts.

14 BITRE (2015). Traffic and Congestion Cost Trends for Australian Capital Cities

15 SRL East (2022). Draft Structure Plan – Community Infrastructure Assessment

16 WHO (World Health Organization) (2017). Urban Green Spaces and Health: A Review of Evidence

Related posts

Dive deeper into insights that matter to you.

Smoke and Mirrors: The Real Cost of Office Incentives

Australia’s Love of Big Homes Was Rational, Until the World Changed

The next flex office wave

Retail on the Rise: Australia’s shopping centre revival

Make smarter decisions

Get in touch with the Team to get an understanding of how we transform data into insightful decisions. Learn more about how Atlas Economics can help you make the right decisions and create impact using our expertise.